By: Anne Gordon, Clinical Professor of Law and Director of Externships, Duke Law School

I’ve often heard colleagues say that they love teaching so much their law school wouldn’t even need to pay them for it . . . but grading is a different story. Grading is time-consuming and stressful, two things that none of us needs as we finish up an uncommonly difficult year. We all know that taking the time to check that stress is good for our health. You may not know that it is also critical for reducing your bias. Mitigating our biases is critical to ensure accurate student assessment, as well as the relationship-building that is so key to our mentorship and supervision. This article, an excerpt from a paper in the Spring issue of the Clinical Law Review, will illustrate how biases shape our thinking, show the link between stress and bias, and provide concrete ways to mitigate our bias – critical for avoiding biased behavior toward our students – in grading season and beyond.

Brains and Bias

Our brains sort through information we encounter in the world by creating schema, automatic characterizations that allow us to go on “auto-pilot” as we process information throughout our day. These allow us to be efficient: we can distinguish a plastic bag from a log in the road while driving and react appropriately, even without conscious thought. Our automatic judgments can also activate in ways that aren’t helpful, however, when those schema intersect with actual or perceived social characteristics like race or gender, including harmful stereotypes.

Humans are also plagued by cognitive biases, other decision-making shortcuts that can lead us to erroneous conclusions. These biases can combine with our stereotype-based biases to produce damaging effects for our students. For example, it is well-documented that humans harbor an Anchoring Bias, the tendency to “anchor” judgments on the first piece of information offered, and Confirmation Bias, the tendency to selectively search for information that confirms prior beliefs or judgments. If you team-teach your clinic, you should also be on the lookout for the Bandwagon Effect. This is our tendency to have our attitudes and beliefs shaped by others, due to our innate desire for social harmony.

It is easy to see how these biases can interact with the stereotype-based bias described above. For example, a professor’s bias may put a student in the schema of “low performing;” if the student then turns in a poor first assignment, the professor’s cognitive bias serves to “anchor” his perception of that student in subsequent interactions. Confirmation Bias then kicks in, and the professor seeks out errors that conform to her initial judgment of the student as being low performing. The teacher “knew” that this student would struggle, and that’s what the professor sees. This is what we seemed to see playing out in a recorded conversation between Georgetown professors – a conversation that got one of them fired. The converse of Confirmation Bias is also true – students judged as competent receive the benefit of a teacher’s subconscious willingness to overlook evidence to the contrary (and may also miss out on opportunities to learn).

The interaction of these effects has been borne out in the research. One study by Dr. Arin Reeves showed how lawyers found more errors in a writing sample that they thought had been written by a Black associate, despite identical errors in a “white-written” sample. The study’s authors concluded that Confirmation Bias caused the partners to look more carefully for errors in the “Black lawyer’s” work, and more easily disregarded errors by the white lawyer, who fit their stereotype of a generally competent professional. While this study has not been replicated among law faculty, it would be easy to see how it could play out in our evaluation of our students.

Stress Amplifies Bias

The conditions of teaching, especially in stressful times, create a perfect storm for our biases to manifest. When we are stressed, low on blood sugar or sleep, or engaging in sustained intellectual engagement (think a stack of student work to evaluate), we become cognitively depleted. Cognitive depletion leads us to fall back on our biases, simply because the associations are already there – even where we might be able to keep those biases in check if we were at our best. Cognitive depletion and stereotype bias feed off each other, where the more stressed we are, the more biased we become. This can take shape in two ways: first, for biased teachers, stress amplifies their bias. But it also means that teachers trying to overcome their bias, or trying to communicate a lack of bias to their students, are taxed in a way that can result in – you guessed it – bias. Studies have shown that the more cognitive resources teachers spend trying to communicate a lack of racism to their students, the more cognitive depletion that results.

Our biases manifest in interactions with our students, in the form of decreased eye contact, nervousness, discomfort, awkwardness, speech errors, stiffness, and other subtle avoidance behaviors that convey dislike or unease, possibly due to fear of being labeled a racist, or fear of being met with hostility by our students. These behaviors, so subtle that they may not be perceptible even as we’re doing them, are therefore less controllable through conscious will – you can’t just will yourself to blink less. Members of minoritized groups, however, can sense the awkwardness, leaving them wondering: was that constructive feedback due to actual performance, or instructor bias? Or was that positive feedback due to professors’ over-correcting their biases, opting or a “great job” instead of giving them the real story about their abilities? This ambiguity is often a contingency of under-represented students’ identity, and ultimately creates a dynamic where students are not fully capable of gauging their own performance, not fully able to accept and make use of our feedback, and not fully able to engage in the learning process.

A Good Time to Make a Change

As we go into our grading, feedback, and evaluation season, therefore, it is imperative that we take affirmative steps to mitigate our bias, and the stress that amplifies that bias. These measures can fall roughly into three categories: the first is addressing our own bias, the second is reducing our cognitive load, and the third is changing our processes. Here’s a useful frame used by psychologist Jonathan Haidt at NYU. The frame here is that in each of us there is an elephant and a rider, walking on a path. The Rider is our rational side; our evidence-based decision-maker. Our Elephant is our emotional side – it acts based on feelings and instincts. The Path is our environment, our systems. Here’s how it works: although the rider holds the reins and appears to lead the elephant, there’s only so long the rider can struggle with the elephant before the six-ton animal just takes over. The elephant might do what the rider wants for a while, but where there’s a struggle, the elephant will always win. Fortunately, because the elephant goes on auto-pilot so often, it’s happy following a path – and it will follow the path of least resistance.

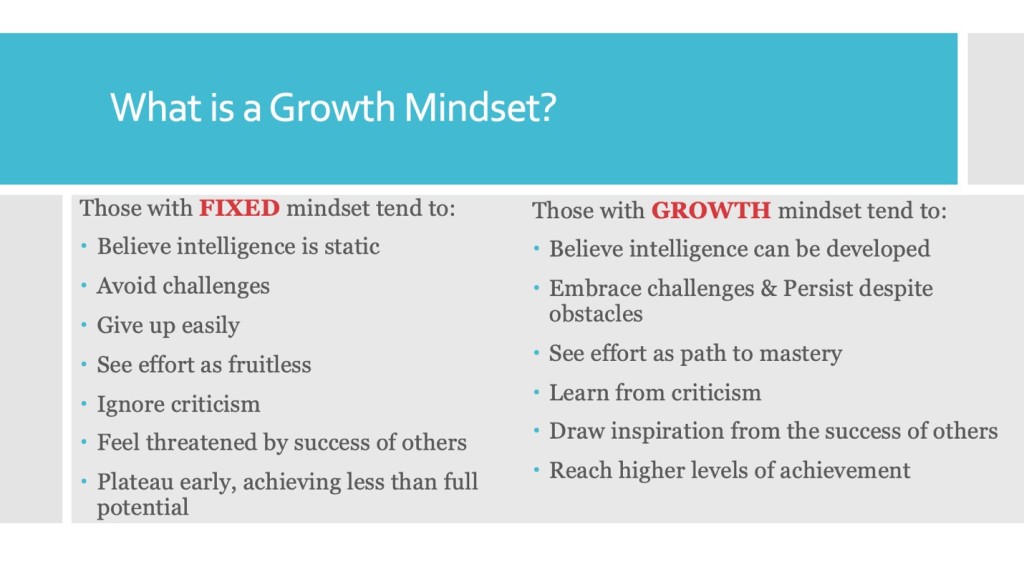

So according to Haidt, in order to change, you need to do three things: tame your elephant, strengthen your rider, and shape your path. The first, taming your elephant, requires mitigating your own bias. This requires sustained work to rid ourselves of negative internalized stereotypes, through training, exposure to cross-cultural diversity, and nurturing a growth mindset (making you less likely to favor only those you’ve identified as “smart”).

Strengthening our rider means stopping ourselves from falling back on our biases – we do this by reducing the conditions that are ripe for bias to present (in other words, reducing cognitive load). One way to do this is through mindfulness practice, which can increase our ability to become aware of our emotions and biases, and therefore better able to engage our self-regulatory processes, so we can act in a manner congruent with our values. Another simple-to-describe (if tricky to implement) way to stop a retreat into cognitive overload (and bias) is to try to reduce the number of cognitively taxing activities before student interactions. Interpersonal stress, impending deadlines, a sleepless night, and even bodily discomfort can lead to cognitive taxation. So try not to schedule an entire day of back-to-back supervision meetings, or a student meeting directly after a stressful faculty meeting. Get extra sleep, exercise, and stretch during your feedback week. Don’t grade student work after watching the news. And here’s more good news: another easy way to re-charge one’s cognitive batteries is to eat a snack. Researchers have proven that some of the effects of cognitive depletion can be undone by ingesting glucose. So go ahead and eat that leftover Easter candy – it’s for your students.

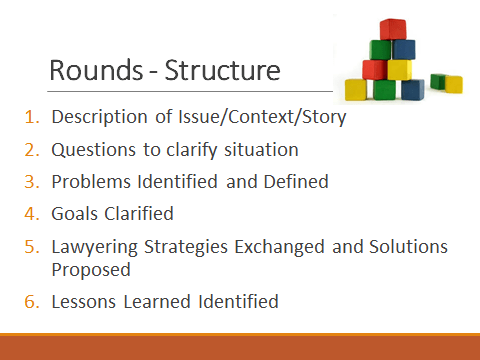

The final way to reduce bias is by shaping the path: de-bias our process. Formulas, or evaluation rubrics, can help mitigate these problems by making performance metrics explicit, concrete, and consistent. In addition to leading to less biased grading, a good rubric will also help the teacher, by easing the pain of a stressful feedback discussion. Where teachers can be precise and name concepts, they can be clear with their feedback. Without such clarity, the message teachers seek to convey for future learning may be muddied, awkward, and cause cognitive strain (which amplifies our bias and impairs our students’ learning).

Those lucky enough to be team-teaching have the good fortune to be able to engage in a practice known as a calibration session, where the individual faculty members write preliminary appraisals of the students, including proposed ratings. Then the faculty meet and show their proposed ratings along with the rationale behind the rating. These sessions have the advantage of mitigating bias in the first place (because faculty are pressed to base their judgments on objective measures) and may cause further elimination of bias when forced to confront their own ratings against others’.

As we round out our semester, reading our final student assignments, scheduling our final feedback conversations, and recording our assessments, it is imperative that we also make the time to check our biases. As you sit down to grade, remember the Elephant, the Rider, and the Path, and do the work required to make your feedback and evaluation fair. Our students deserve it.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Tagged: assessment of teaching and learning, implicit bias in the classroom, legal education | 2 Comments »