By Robert Kuehn, Washington University School of Law

In 1980, one-third of law students and only 14% of all law teachers were female, and a mere 9% of students and 4% of faculty were identified as non-white. Today, law faculties are more diverse by gender and race/ethnicity. Yet, the demographics of faculty subgroups diverge widely and, importantly, faculty remain less diverse than their students.

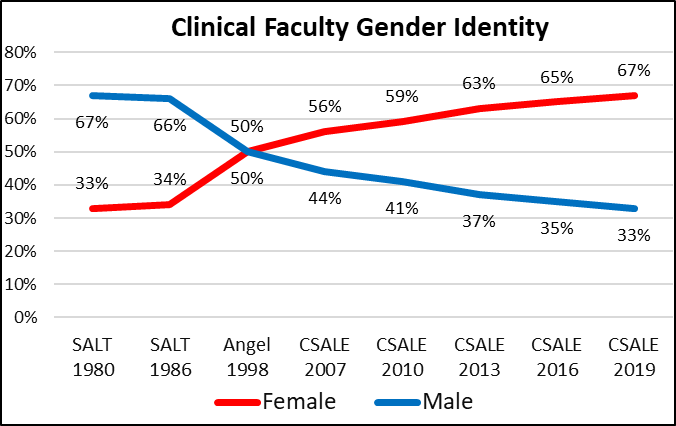

Focusing principally on law clinic and field placement teachers (full time, excluding fellows), over two-thirds identified as female (cis or trans) in the latest 2019-20 Center for the Study of Applied Legal Education (CSALE) survey. The graph below reflects a trend of increasingly female clinical faculty beginning in the late 1980s/early 1990s and continuing through all five tri-annual CSALE surveys:[1]

Newer clinical teachers are even more predominantly female ─ 73% of those teaching three years or less are female. Within clinical teaching areas, those who primarily teach field placement courses are more predominantly female than those who primarily teach in a law clinic — 82% of field placement teachers are female compared to 65% of clinic teachers.

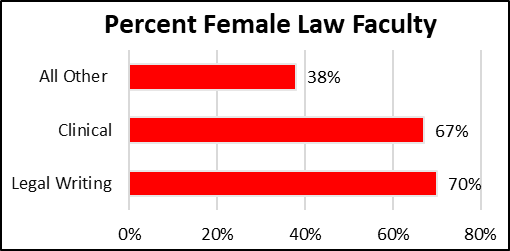

By comparison, 47% of all full-time law teachers were identified as female in 2020 law school ABA annual reports, an increase from 40% in 2011, 32.5% in 2000, and 24% in 1990. However, ABA results include the overwhelmingly female clinical and legal research and writing faculties. If clinical (67% female) and legal writing (70% female) faculty are removed from the 2020 ABA totals, women constitute fewer than 38% of full-time non-clinical/non-legal writing faculty, as illustrated below.[2] In contrast, 54% of J.D. students in 2020-21 were female, compared to 47% in 2010, 48% in 2000, 43% in 1990, and 34% in 1980.

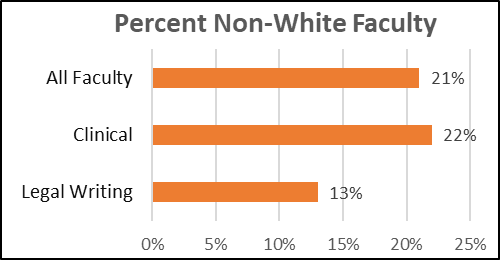

Faculty have increased in racial and ethnic diversity since 1980. The percentages of full-time clinical teachers by race/ethnicity are shown in the table below. Surveys indicate steady, but slow, growth in the percentage of full-time non-white clinical teachers (excluding fellows) over the last four decades.

| Clinical Faculty Race/Ethnicity | SALT 1980[3] | SALT 1986 | AALS 1998[4] | CSALE 2007 | CSALE 2010 | CSALE 2013 | CSALE 2016 | CSALE 2019 |

| White | 95% | 92% | 87% | 87% | 86% | 83% | 80% | 78% |

| Non-White | 5% | 8% | 13% | 12% | 13% | 15% | 17% | 18% |

| Other/2 or More Races | ─ | ─ | <1% | 1% | 1% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

Among newer clinical teachers of three years or less, the percentage of white teachers was slightly lower at 76%. Within clinical teaching, 77% of primarily law clinic instructors and 83% of primarily field placement teachers are white.

In the 2020 annual reports, 21% of full-time law faculty were identified by their schools as “minority,” an increase from approximately 17% in 2011, 14% in 2000, and 10% in 1990. The most recent ALWD/LWR survey identified 13% of legal research and writing faculty as non-white, multiracial or other, compared to 12% reported non-Caucasian in its 2010 survey.

Similar to gender, law school faculty are less racially/ethnically diverse than their students: 34% of students were identified in 2020 annual reports as minority, an increase from 24% in 2010, 21% in 2000, 14% in 1990, and 9% in 1980.

Available surveys and reports do not include recent information on the age of law faculty. There has been no change, however, over the five CSALE surveys since 2007 in the median number of years of prior practice by those teaching full time in a law clinic or field placement course, remaining approximately eight years. Excluding those hired into temporary fellow positions, similarly across CSALE surveys the median number of years of prior practice experience among newer faculty teaching three years or less in a law clinic or field placement course has been eight years.

In sum, while the diversity of law school faculty has been increasing over the past four decades, it still lags behind the gender and racial/ethnic diversity among students. And even though schools are hiring increasingly more female faculty, women continue to be disproportionately hired into traditionally lower status/lower paying clinical and legal writing positions.[5] There may be no easy fix to these issues, but the first step towards addressing them is to be aware of the numbers.

[1] “SALT” percentages are from Richard H. Chused, Hiring and Retention of Minorities and Women on American Law School Faculties, 137 U. Pa. L. Rev. 537, 556-57 (1988) (also reporting 14% of all law teachers as female and 5% as non-white in 1980). “Angel” percentages are from Marina Angel, The Glass Ceiling for Women in Legal Education: Contract Positions and the Death of Tenure, 50 J. Legal Educ. 1, 4 (2000).

[2] The 2020 ABA annual reports identified 4,399 female and 4,986 male full-time faculty (5 reported as “other”). Removing 1,157 female clinical teachers (67% of the 1,727 full-time clinical faculty reported by the 95% of schools that participated in the CSALE survey) and 649 female legal research and writing teachers (70% of the 927 full-time LRW faculty at the 169 of 203 ABA schools that participated in the 2019-20 ALWD/LWI Legal Writing Survey) results in 2,593 full-time female non-clinical/non-legal writing faculty. Further removing 848 male faculty identified in the CSALE and ALWD/LWI surveys results in 38.5% full-time non-clinical/non-legal writing female faculty. If the missing 5% of schools in the CSALE survey and 17% in the ALWD/LWI survey are accounted for, 37% of 2020 full-time non-clinical/non-legal writing faculty were female.

[3] The 1980 and 1986 SALT surveys excluded faculty from minority-operated schools and, therefore, likely underrepresented non-white faculty.

[4] “AALS” percentages are from an AALS Clinical Section database reported in Jon C. Dubin, Faculty Diversity as a Clinical Legal Education Imperative, 51 Hastings L.J. 445, 448-49 (2000). [1] Robert R. Kuehn, The Disparate Treatment of Clinical Law Faculty (2021), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3760756.

[5] Robert R. Kuehn, The Disparate Treatment of Clinical Law Faculty (2021), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3760756.

Filed under: Best Practices, Best Practices and Clinics, Catalysts For Change, Diversity & Social Justice, Uncategorized | Tagged: best practices for legal education, clinical law faculty, clinical legal education, CSALE, Equity, gender pay equity, gender race and employment in legal academy, law professor salaries, law professor status, law professors, law school, legal education, legal education reform, legal writing professor equity, salary equity, status in legal academy, unequal profession | Comments Off on Shifting Law School Faculty Demographics

Looking forward to DAY 2 and more lessons.

Looking forward to DAY 2 and more lessons.