The presidential election campaign this year has provided several teachable moments for law students and lawyers and this post focuses on one of them.

Unless you have been hibernating for the past few weeks, you know that a number of women have accused Republican candidate Donald J. Trump of sexual misconduct. Mr. Trump and his supporters have denied the claims, arguing that the fact that the women did not complain at the time of the alleged incidents undermines their credibility.

Rather than focusing on the merits of these particular claims, this post uses dispute resolution literature to describe why people often don’t complain, especially about sexual misconduct and discrimination. Then it discusses implications for defense counsel and their clients of the lack of complaints by people with potentially valid claims. And finally it offers some hypothetical situations for law students to consider about how they would act when representing defendants.

Naming, Blaming, and Claiming

The following two classic, companion articles analyze how complaints do or do not occur. William L. F. Felstiner, Richard L. Abel, & Austin Sarat, The Emergence and Transformation of Disputes: Naming, Blaming, Claiming . . . , 15 Law and Society Review 631 (1980-81); Richard Miller & Austin Sarat, Grievances, Claims and Disputes: Assessing the Adversary Culture, 15 Law and Society Review 525 (1980-81).

To illustrate the evolution of disputes, consider the case of Lilly Ledbetter v. Goodyear. Ms. Ledbetter worked for Goodyear from 1979 until she retired in 1998. Shortly before she retired, she received an anonymous note with the salaries of three men doing the same job as she did but who earned 15% to 40% more than her. She sued Goodyear and the jury awarded her about $3.3 million, which was later reduced to about $300,000. In 2007, in a 5-4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that she could sue only for actions occurring within the prior 180 days, and that she did not prove that discrimination occurred within that period. In response, Congress enacted the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, providing that the statute of limitations for presenting an equal-pay lawsuit begins on the date that the employer makes the initial discriminatory wage decision, not at the date of the most recent paycheck.

Naming – “Perceiving Injurious Experience” (PIE). The first step is that potential complainants must perceive that they have suffered an injury. Until Ms. Ledbetter received the anonymous note, she did not perceive that she had experienced an injury. After receiving the note, she perceived that she had been injured by receiving lower compensation than similarly situated men.

I picked the Ledbetter case because it dramatically illustrates this first step in the process that can lead people to complain (or not). Many other situations aren’t so clear. If someone bumps into you in public, for example, you may feel that your body or dignity has been injured – or you may just write off the experience as a normal part of life.

What is perceived as injurious is subjective and a matter of social definition. In the Mad Men era, before sexual harassment was legally and socially recognized as wrong, for example, female employees experienced bosses’ sexual conduct as a hazard but not the source of personal injury.

There are individual differences in propensity to perceive things as injurious. Some people regularly feel victimized by a lot of things that others would simply accept without much thought.

Some, including the courts, might not recognize certain experiences as injuries but people may feel that they were injured nonetheless.

Blaming – Feeling Grievance. Blaming is the next step in what Felstiner et al. call the “transformation” of PIEs into disputes. Blaming is when a person believes that someone or some entity is at fault for the person’s perceived injury. Of course, people don’t always blame someone else for their injuries. Instead, they may consider an injury as just a fact of life, an act of God, or their own fault. Sadly, some blameless victims blame themselves for acts that abusers are solely responsible for. And people sometimes unfairly blame others for things that the others are not responsible for.

In Ms. Ledbetter’s case, once she learned of the disparity in pay, she blamed Goodyear, her employer. While this may seem like an obvious response these days, we used to justify paying men more than women on the theory that they had to support their families. Given that mindset, many women accepted that this was just “the way things are” and didn’t particularly blame their employers.

Claiming – Demanding Redress. Of course, when people blame others for their perceived injuries, they may demand some form of redress. These demands may take many forms such as payment of money, restoration of the prior status quo, cessation of injurious behavior, and apologies, among others.

Sometimes people make claims even when they don’t believe that they are injured and/or don’t blame others. For example, people who commit insurance fraud presumably don’t believe that they have been injured but demand payment. Indeed, some wealthy individuals and business fear (sometimes with good reason) that some people file fraudulent claims against their targets assuming that the claimants can get payments to make them go away.

In Ms. Ledbetter’s case, she demanded payment from Goodyear. However, people who blame others may make no demands for many reasons. Some believe that it wouldn’t be worth the effort because they believe that their demands wouldn’t be satisfied or the time and effort required would outweigh the benefit. Some fear negative consequences such as retaliation or damaged reputations. For some, the process of pursuing a remedy would keep them stuck in dealing with the problem when they would just prefer to move on with their lives.

Disputing – Pursuing Rejected Demands. Some people respond to complaints by promptly taking action satisfying the complainants, at least enough for the complainants to stop pursuing their complaints. Of course, some people reject the complaints in whole or part and the complainants continue to pursue the complaints. Pursuing unsatisfied complaints is disputing.

In Ms. Ledbetter’s case, Goodyear did not satisfy her demands and she pursued the dispute all the way to the Supreme Court. Sometimes unsatisfied complainants consult lawyers and/or file lawsuits, but not always. In addition, complainants may drop complaints for many of the reasons that some people do not make complaints at all.

Empirical Data on Naming, Blaming, and Claiming. The Miller and Sarat article presents data from the classic Civil Litigation Research Project about patterns of naming, blaming, and claiming in what they call “middle-level” disputes, i.e., those involving claims of at least $1000. (When the data were collected in 1980, this was the equivalent of almost $3000 in today’s dollars.) The article uses helpful graphics of pyramids to illustrate the patterns of attrition as some people who blame others do not complain, and some complaints do not turn into disputes, and some complaining disputants do not consult lawyers or file suits.

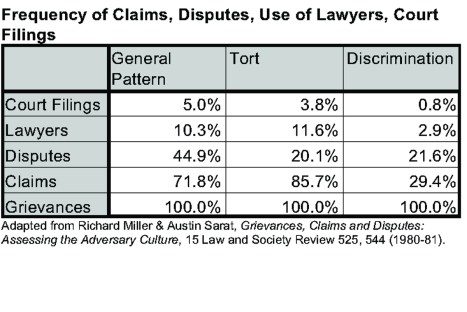

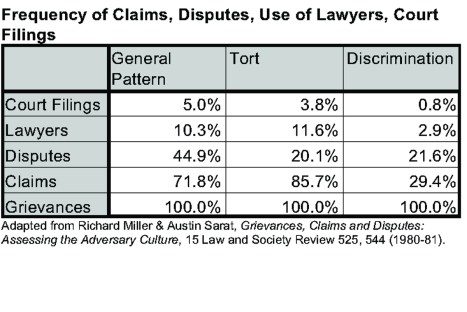

The following table shows how patterns of attrition vary in different types of problems. The data refer to the percentages of situations for people who perceive injuries. It shows the percentages of these situations that lead to complaints, disputes, and use of lawyers and court.

The general pattern in the study was that 71.8% of grievances became complaints against others, 44.9% of the grievances were disputed, in 10.3% of the grievances the grievants consulted lawyers, and in only 5.0% of the grievances, the grievants filed lawsuits.

For situations that would be considered torts, there was a higher percentage of situations that turn into claims (85.7% vs. 71.8%) and a much smaller percentage that turned into disputes (20.1% vs. 44.9%).

The pattern in situations involving perceived discrimination was quite different. There was a lower-than-average incidence of complaints (29.4% vs. 71.8%). However, almost three quarters of discrimination complaints turned into disputes (21.6 / 29.4) whereas less than a quarter (20.1 / 85.7) of tort complaints were disputed.

What accounts for this difference? For torts, the insurance system is designed to receive and resolve complaints and there generally isn’t much stigma or risk of retaliation for filing complaints. For the large number of relatively small complaints, insurance companies and other defendants typically prefer to pay the claims promptly than spend resources disputing them.

People with discrimination grievances may doubt that they will receive satisfaction by making complaints. Issues of discrimination often are ambiguous and difficult to prove. Filing complaints may invite scrutiny of the grievants’ own behavior. Indeed, employees often are wary of being branded as “troublemakers” and this may be particularly true for discrimination complaints. They risk subtle and not-so-subtle forms of retaliation, which could make their situations worse. So the low rate of complaining should not be surprising. People who have decided to complain presumably have decided to do so despite the risks just noted and once they have done so, they may be particularly determined to pursue their claims.

The data analyzed by Miller and Sarat is more than 35 years old but I suspect it generally reflects modern reality. I haven’t looked for recent studies, but if you know of any, please share them in a comment below.

Complaining About Sexual Misconduct

Since the publication of the Access Hollywood tape of Mr. Trump’s comments about his interactions with women, a number of women have come forward publicly to describe what they experienced as sexual misconduct by Mr. Trump. He has categorically denied all the claims, argued that the women have improper motives, and threatened to sue the complainants. He has argued that the fact that they did not make any demands on him soon after the alleged incidents casts doubt on the veracity of their claims. I do not express any opinion here about the merits of the particular claims about and by Mr. Trump.

Instead, let’s consider why people who perceive that they have been injured by sexual misconduct often would not make demands on the people who committed those acts.

The Trump controversies have prompted an outpouring of reaction by women who felt injured but didn’t press any claims as well as by analysts of these phenomena. Columnist Dahlia Lithwick provided an historical review, which may be particularly useful for younger law students.

Clearly, many women identified with the experiences described by Mr. Trump’s accusers. Soon after the Hollywood Access tape was released, author Kelly Oxford tweeted, “Women: tweet me your first assaults,” under the hashtag #notokay. Within a few days, 27 million people had responded. Similarly, the hashtag #Whywomendontreport has also attracted a lot of responses. Many women never told anyone of their perceived injurious experiences except perhaps some close friends or relatives.

In an article entitled Women Know Why Donald Trump’s Accusers Stayed Silent for So Long, Rachel Sklar wrote, “Women who dare to come forward to report stories of being sexually molested find their stories doubted, their behavior questioned, their credibility impugned. Did they imagine it? Do it for the attention? Were they lying about it (because reporting sexual assault is always the path to riches and respect, right?) Why didn’t they stop it? The litany of responses is familiar by now: You were flirting, weren’t you? What were you wearing? My, that was a short skirt. Wait, were you drinking? Boys will be boys! . . . This is grotesquely magnified when accusations are leveled at famous or powerful men. . . . Not only are women expected to receive and submit, but they are expected to laugh off behavior that is otherwise invasive and threatening, to ‘not make a big deal’ about it.”

Mr. Trump’s attacks on his accusers reflect a general fear about complaining. Liz Plank wrote that “Trump isn’t just trying to attack these women; he’s signaling to others who may come forward. By metaphorically naming and shaming them, and implicitly inviting his followers (who have a history of horrifying harassment) to do the same, he wants to terrify any other women from coming forward too.” Indeed, Mr. Trump has threatened to sue his accusers. This reinforces a message to women that it generally is dangerous to complain even when there aren’t explicit threats.

Slate writer Christina Cauterucci wrote, “Female friends and acquaintances, including several Slate colleagues, have told me that Trump has resurfaced deeply buried or forgotten memories of sexual assault, some stretching back to childhood. . . .Trump has also caused some women I know to rethink past sexual violations they’d previously explained away to themselves as misunderstandings or petty instances of ‘boys being boys.’ Trump’s talk and his accusers’ allegations are awakening long-dead zombies in our memories, forcing us to confront assaults we’d never labeled as such.”

The Miller and Sarat data and the recent outpouring of personal testimonies demonstrate the low level of complaining about perceived sexual misconduct and discrimination.

This is a serious problem for many reasons. It is simply wrong that large classes of people feel injured but are too intimidated to present their claims. This violates our notions of procedural justice, which are based on the assumption that people have reasonable opportunities to complain and be heard fairly. Although some of unclaimed grievances may not be valid, presumably a substantial proportion of the grievances have real merit. Even people with good-faith claims that are not valid are entitled to present them. The wrongdoers’ pattern of behavior violates our social policy embodied in laws to protect people from sexual assault and discrimination. Meritorious grievances that are not pursued constitute an undeserved transfer of wealth to wrongdoers from the people they have victimized. And the low level of enforcement of legal protections effectively encourages people to continue a pattern of wrongful behavior because of the low probability that victims will complain.

These are complex problems that deserve serious efforts for social remedies. These issues are beyond the scope of this post, however.

Implications for Defendants and Defense Counsel

In our legal system, parties are assumed to advance their own interests, not advance any other party’s interest or social policy. Under the logic of the adversary system, it is up to would-be plaintiffs to complain if they wish, on the assumption that truth and justice will be produced through the adversary process.

This theory may approximate reality when the parties have roughly equal power and there aren’t serious impediments to use of the system.

The theory doesn’t work so well when there is a serious mismatch of power and social deterrents to use of the dispute resolution system as in the case of many sexual assault and discrimination grievances.

Of course, would-be defendants have no duty to encourage grievants to bring complaints against them. Indeed, that would seem crazy in what Professor Jonathan Cohen calls The Culture of Legal Denial, 84 Neb. L. Rev. 247 (2005), where the “normal practice within our legal culture is for injurers to deny responsibility for harms they commit.”

Indeed, some defendants and their lawyers regularly use the Bart Simpson defense strategy: “I didn’t do it, nobody saw me do it, there’s no way you can prove anything!”

Defense counsel may take any legally permissible actions to resist charges against their clients. ABA Model Rule of Professional Conduct 3.1 states: “A lawyer shall not bring or defend a proceeding, or assert or controvert an issue therein, unless there is a basis in law and fact for doing so that is not frivolous . . ..” Rule 4.4(a) states: In representing a client, a lawyer shall not use means that have no substantial purpose other than to embarrass, delay, or burden a third person . . ..” Tactics that are not prohibited are permitted.

Mr. Trump frequently has used litigation, as documented by USA Today, and frequently has threatened suit, as he did with the accusers of sexual misconduct and the New York Times for publishing an article about two of the accusers. The American Bar Association declined to publish a report on Mr. Trump’s litigation history reportedly out of fear he would sue them (though ABA officials say that the report violated its policy of being non-partisan).

According to the Washington Post, “When Donald Trump has needed a legal brawler, he has often turned to Marc Kasowitz, a hard-edged Manhattan attorney whose website cites a description of him as one of the most ‘feared lawyers in the United States.’” The general counsel for one of Mr. Kasowitz’s clients was quoted as saying, “When there’s a tough, call it rough-and-tumble kind of litigation, those are the guys I would go to. . . . They’re not afraid to get their hands dirty.”

Of course, many defendants and their lawyers routinely take tough positions in litigation, which is considered normal in our legal culture. Should they act any differently in cases involving sexual misconduct or discrimination because of the greater vulnerabilities described above?

As a matter of legal ethics, going easier on such (would-be) plaintiffs would be problematic because of lawyers’ duty of loyalty to their clients.

Yet some lawyers may find it distasteful to aggressively litigate against such vulnerable parties, especially if they believe that their claims are valid. Rule 1.16(b)(4) states that a lawyer may withdraw from representation if “the client insists upon taking action that the lawyer considers repugnant or with which the lawyer has a fundamental disagreement.” Although withdrawal is possible under these circumstances, probably very few lawyers take this route.

Practical Ethics Hypos

The following are hypothetical questions for law students to consider. Although they might seem most appropriate in professional responsibility courses, they go beyond technical issues of legal ethics. Professors might also use them in a range of legal practice courses as well as courses on gender, discrimination, and business operations, among others.

These questions involve businesses in which you, as their lawyer, have strong evidence that they have committed wrongdoing against vulnerable parties. Although this post has focused on allegations against Mr. Trump, the following questions do not involve him because people have such strong feelings about him that responses may be colored by those feelings.

Instead, consider run-of-the-mill corporate giants or substantial mid-size firms. Focus primarily on grievances by people who perceive that they have been injured by sexual misconduct or discrimination committed or approved by high-level business leaders.

In a case of alleged serious sexual misconduct that you believe occurred as alleged, which, if any, of the following tactics would you use?

- Use the Bart Simpson strategy, essentially taking the approach for your client, “He didn’t do it, nobody saw him do it, there’s no way you can prove anything!”

- Vigorously and visibly investigate the accuser’s past, in part to intimidate her from pursuing her claim.

- Interview the accuser’s family, friends, and associates about the alleged incident, in part to embarrass the accuser and pressure her to drop the case.

- Make public statements consistent with your legal position, challenging the accuser’s motives, character, and behavior.

- Vigorously litigate the case, increasing the accuser’s costs and dragging out the process, in part to pressure her to accept a heavily discounted settlement.

- Threaten to sue the accuser for defamation or actually do so.

- Take actions that may violate the ethical rules but that are commonly used in practice and are unlikely to result in professional discipline or malpractice liability.

What other actions might you be willing to take or not in this case? What principle distinguishes actions that you would or would not take? How would your responses differ, if at all, if the case involved other issues such as fraud, product liability, health and safety violations that business leaders initiated or at least knew about and failed to stop and that involved plaintiffs with relatively few resources?

Now add the following assumptions to the preceding hypothetical case. You are a recent law graduate, a year into practice, and you have a job with a law firm that regularly represents large businesses. The job market is tight and you feel lucky to have your job. You like your job and hope to become a partner in the firm by demonstrating your abilities and value to the firm and its clients. You generally are comfortable with the positions your firm takes on behalf of its clients but you feel uncomfortable in this case. You are afraid of the reaction by senior lawyers in the firm if you express your concerns or suggest withdrawing because the client is a major client for your firm and it adamantly wants to pursue a hard-line strategy to discourage other possible plaintiffs from filing suit.

How do these assumptions change your responses to the preceding questions, if at all? What can you do to preserve both your professional opportunities and your personal integrity?

Discuss.

Filed under: Best Practices, Diversity & Social Justice, Diversity & Social Justice | Comments Off on Why Don’t People Complain? Implications for Defense Counsel. And Some Practical Ethics Hypos for Students.