By Robert Kuehn, Washington University School of Law

The ABA first adopted standards for accreditation of law schools in 1921. But, as explained in a recent article by my colleague Peter Joy,[1] it was not until 1993 that schools were required to provide a program of education that would prepare students for the practice of law, not simply for admission to the bar. And not until 2005 did schools have to begin to ensure that each J.D. student receives instruction in the professional skills necessary for effective participation in the legal profession. Even then, the ABA determined that a student needs only “one solid credit” hour of skills training to be considered adequately prepared to begin the practice of law.

Since the adoption of a professional skills requirement, law school enrollment has declined precipitously, graduates have struggled to find employment, and bar passage rates have dropped in many states. In the midst of this turbulent period, in 2014 the ABA recognized the inadequacy of its one-credit skills requirement and adopted a six-credit experiential requirement that will apply to graduates starting next year. With a decade of mandatory professional skills training now completed, it is a good time to examine enrollment trends in law clinic, externship, and simulation courses over the past ten classes of law students.

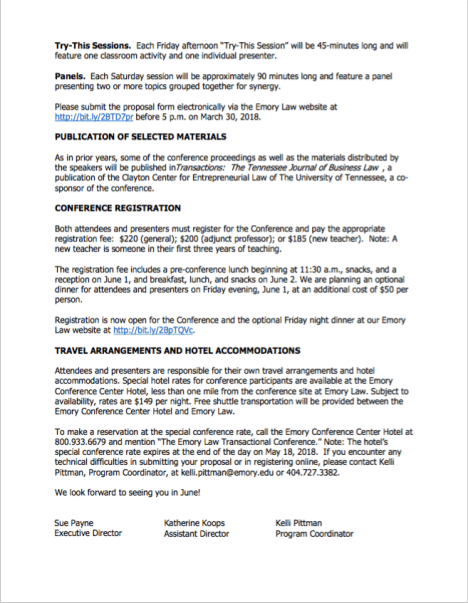

Reviewing data submitted to the ABA in annual questionnaires certified by each school’s dean to be true, accurate, and complete,[2] there has been significant growth in enrollment in experiential courses since academic year 2005-2006. Total enrollment in law clinic, externship, and simulation courses has increased by almost 25% over the past ten years,

Some of the growth before 2011 might be attributable to increased law school enrollment. But, as seen below, the rate of increased participation in experiential courses has far outpaced law school enrollment, which is down by over 20%. It is also of note that the growth in experiential course enrollment started even before the first group of graduates were subject to the new one-credit professional skills requirement so this increased enrollment was fueled by much more than that requirement.

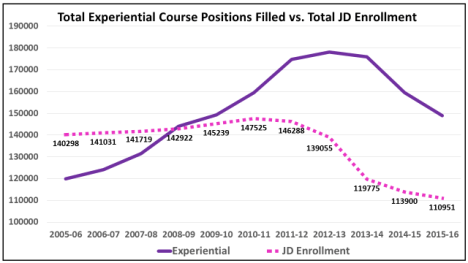

This experiential course growth independent of law school enrollment is illustrated in the next two graphs, which track enrollment growth per upper-level student. Although down slightly the last few years, upper-level students enrolled in an average of 2.06 experiential courses in 2015-16, a 57% increase in enrollment per student over the ten-year period.

Law clinic and externship enrollment reflect this growth. Clinic enrollment is up 57% and externship up 74% (the ABA stopped requiring schools to report actual law clinic positions “filled” after 2016; only purported positions “available” is now reported). Enrollment in externships has always exceeded clinic enrollment but was particularly strong beginning in 2011, a time when graduate employment rates dropped significantly.

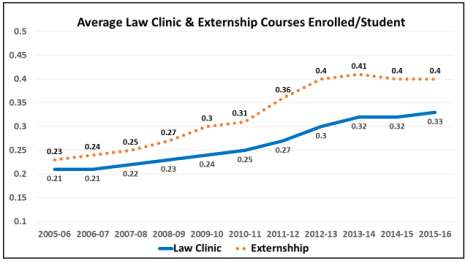

Some have suggested that the recent drop in bar passage may be due to increased enrollment in experiential courses and the possible substitution by students of skills courses for typical doctrinal coursework. However, the next graph indicates that bar passage rates were fairly steady from 2006-2013,[3] a time when experiential course enrollment increased by over 50%, and the recent decline in bar passage coincided with decreased experiential enrollment. In addition, David Moss (Wayne State) and I will be publishing the results of our joint study of ten years of law graduate performance on the bar exam which finds no association (positive or negative) between taking experiential courses and passing the bar.

Others posit that rather than the increase in experiential course enrollment, the bar passage decline may be due to the decreased LSAT credentials of entering J.D. students, an association seen in the next graph plotting the median LSAT of entering students against bar exam results three years later.

When the ABA was debating the increase in required experiential coursework in 2014, it also considered a request to require every student to obtain a real-life practice experience through a law clinic or externship. Although the ABA declined to require every J.D. student to graduate with a clinical experience, there has nonetheless been a dramatic increase in the number of schools that require or guarantee enrollment in a law clinic or externship course before graduation, increasing from just 12 schools in 2005 to 68 in 2017:

Because of the growth in available positions for students in law clinic and externship courses over the past decade, many more schools also could easily require or guarantee a clinical experience to every student. In their most recent reports to the ABA, 90% of schools had sufficient capacity in their existing law clinic and externship courses to adopt a requirement or guarantee without adding any additional courses or slots for students. Yet, only 33% of schools currently ensure that each graduate may have a clinical experience in spite of evidence showing that a clinical experience can be provided to all students without the need to increase tuition.[4]

It took the ABA over 70 years to recognize that the purpose of law schools, like all other professional schools, is to prepare its graduates for successful entry into their profession, not just success on a licensing exam. The recent adoption of a skills requirement was an important step toward that preparation. But, a mere six credits is hardly sufficient training in the “professional skills needed for competent and ethical participatin as a member of the legal profession” that the accreditation standards require.[5] Let’s hope it’s not another 70 years before law students are finally provided the enhanced professional skills training that they truly need to successfully begin the practice of law and is common in other professional schools, including a mandatory clinical experience for all graduates.

[1] Peter A. Joy, The Uneasy History of Experiential Education in U.S. Law Schools, ___ Dick. L. Rev. ___ (forthcoming 2018), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3129111.

[2] Enrollment data available at http://www.abarequireddisclosures.org (2011-2017) and ABA-LSAC Official Guide to ABA-Approved Law Schools (2005-2010).

[3] Bar exam statistics available at http://www.ncbex.org/publications/statistics/statistics-archives.

[4] Robert R. Kuehn, Universal Clinical Legal Education: Necessary and Feasible, 53 Wash. U. J.L. & Pol’y 89 (2017), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2942888.

[5] Am. Bar Ass’n, 2017-2018 Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools, Std. 302(d), available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_education/resources/standards.html.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Comments Off on Mandatory Professional Skills Training: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been